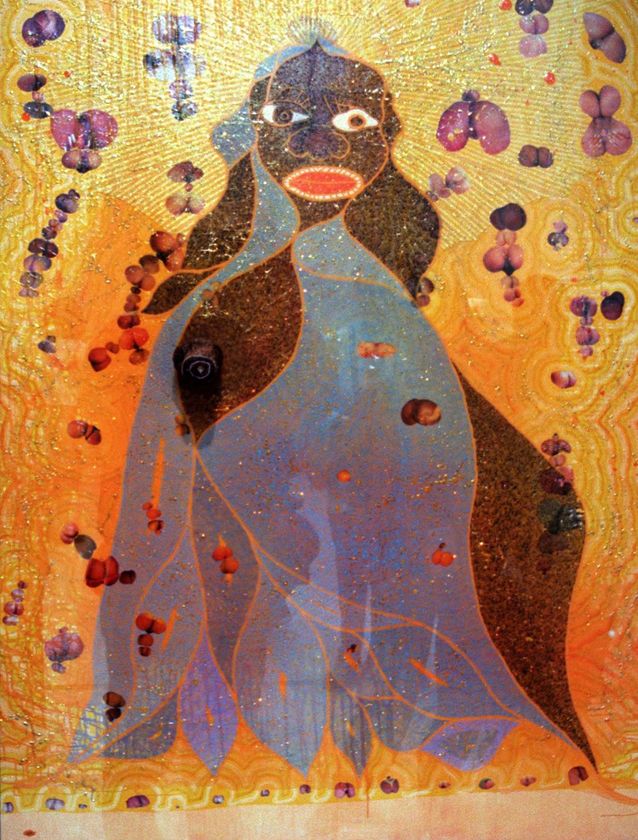

Chris Ofili: The Holy Virgin Mary (1996)

'Modern Master of radiant colour' - Daily Telegraph

Chris Ofili (1968) a renowned British artist of Nigerian heritage, was born and raised in Manchester and studied at the prestigious Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art. He is a Turner Prize Winner and is one of the few black members of the “Young British Artists”, a term coined by the Saatchi Gallery in 1992 referring to prolific artists who incorporate shock tactics in their work.

In his art (which is largely collage based), Chris draws in elements of his African heritage, working with materials such as resin, paint and glitter. It is also often splattered with elephant dung; although Ofili claims that the dung is “tactfully arranged”. His art explores pornography, ‘blaxploitation’ and racial/sexual stereotypes, often sparking controversial outcry like “The Holy Virgin Mary” display in the 1999 Sensation exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York. It was a consciously shocking image which endeavoured to de-Westernize the quintessentially white, Renaissance figure and propel viewers towards supposed illumination.

This infamous collage depicted the Virgin Mary as a very black woman, with a broad nose and thick lips, surrounded by cut outs of pornographic images, female genitalia and images from blaxploitation films;, formed into small cherubims and seraphims. The mantle of her blue robe is opened to reveal a breast composed entirely of elephant dung. The collage also rests on two mounds of elephant dung on either side inscribed with the words, ‘Virgin’ and ‘Mary’.

Perhaps its sheer grotesqueness (in which visual dissonance and distortion are exploited), aimed at pushing the viewer to move beyond the superficially beautiful plane that is so prevalent in Renaissance art (in which the Madonna resembles a more placid Kate Winslet) and onto a higher stratum of divine contemplation.

This raises a few questions:, What exactly is this divine contemplation and what caused such an objection? Was it the ‘Africanization’ of one of the ultimate Western biblical icons, or his idiosyncratic use of dung that “defiled” a holy figure? Probably the former, seeing as other erstwhile artistic materials have been more scandalous. Was it for the purposes of some sort of deeper spiritual connection with the Virgin Mary?; Are Africans supposed to be able to identify with this biblical titan now moreso because she is Black?

According to a critic, ‘Ofili uses elephant dung to connect her in a basic way to the African earth and its people. After all, Mary is as much theirs (Africans') and his (Ofili's)’. This statement causes some unrest within me although I cannot quite pinpoint the locus of offense:. In saying ‘Mary is as much theirs’, is this critic somehow suggesting that whilst we are allowed to worship the figures of Westernised religion, a practise which has been oh-so-generously bestowed unto us, there is no scope for interpretation, at least on our part? We must accept what we’ve been given submissively and without question? I won't even begin to try to dissect the critic's perverse association of dung with African people.

Remember in 1989, Madonna and the black Jesus in ‘Like a Prayer’ and the hullabaloo that inevitably ensued. Would Africans be affronted if Damien Hirst depicted Amadioha or Shango as Caucasian, complete with opalescent skin, aquiline nose and thin lips? Or even a more modern iconic figure like Fela Kuti or Bob Marley?

This painting has since been the victim of vandalism, misinterpretation, harsh criticism and even harsher invectives. It is by no means a masterpiece and the only source of marvel, on my part at least, is how this work has managed to remain in existence until now.

‘It’s about the way the black woman is talked about in hip-hop music. It’s about my religious upbringing, and confusion about that situation. The contradiction of a virgin mother. It’s about the stereotyping of the black female… It’s about beauty. It’s about caricature. And it’s about just being confused.’

Chris Ofili features at Tate Britain - Ending May 16 2010

'Hip, cool and wildly inventive' - The Guardian

Chris Ofili’s paintings are on show at Tate Britain in a major survey of the artist’s career. One of the most acclaimed British painters of his generation, Ofili won the Turner Prize in 1998 and represented Great Britain at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003.

Ofili's early works draw on a wide range of influences, from Zimbabwean cave painting to blaxploitation movies, fusing comic book heroes and icons of funk and hip-hop. These are presented alongside current developments which continue to draw on diverse sources of inspiration, and are full of references to sensual and Biblical themes as well as explore Trinidad’s landscape and mythology.

Highlights include No Woman, No Cry, 1998, a tender portrait of a weeping female figure created in the aftermath of the Stephen Lawrence inquiry and The Upper Room 1999–2002, a darkened, walnut-panelled room containing thirteen canvases depicting rhesus macaque monkeys. Each is differentiated in bold colours, and individually spot-lit.

No comments:

Post a Comment